15

On Castle Walls

Lady Stamforth had been very, very kind, welcoming them to her home and personally showing them to their bedchambers in the quite unassuming but pretty modern stone house which stood within the walls of the great Mediaeval edifice, looking onto the huge expanse of smooth green lawn that was Stamforth Castle’s centrepiece. Well to its rear, the great stone ruin of the central keep loomed in a central position, and over to the far left two Perpendicular buildings, a large hall and a chapel, featured. The walls of Stamforth Castle enclosed an area that was large enough to have housed a small village and, as a knowledgeable Major-General Cadwallader who seemed to be permanently in residence readily informed them, in the earliest days of the great pile’s history very probably had.

Charming and pleasant though Lady Stamforth was, Eudora was frankly at a loss to know why she had invited them. It could scarcely have been in order to promote he Portuguese uncle’s interests, for General Baldaya was not there! The only persons in residence were the Viscount and his lady themselves, their children, the children’s governess, one Miss Gump, who appeared to have nothing in common with Miss Hewitt save their mutual profession and a partiality for Mediaeval architecture, Lady Stamforth’s little brother and sister, the aforesaid Major-General Cadwallader, and the stout Mr Tobias Vane, Stamforth’s cousin.

True, it would have taken the average guest, given Lady Stamforth’s three marriages, quite a portion of the time allotted to the visit to work out who, or rather whose, the assorted children were, but Eudora, for one, did not bother to spend her time on the matter. Raffaella, however, very much intrigued, for in some ways it was not at all unlike the household she was used to, soon had it all at her fingertips. The child known as Clara Vane, perhaps ten years of age, was not the daughter of either of them! she confided. Kindly Eudora forbore to tell her she was not interested, and let her prattle on. At least it was a harmless topic.

The castle was infested with pug-dogs, but then, Eudora seemed vaguely to recollect, the P.W., even in the days when she had been Lady Benedict, had usually had a pug or two about her, had she not? There had certainly been an incident of Eloise, a grim sparkle in her eye, arriving at Lady Harold’s one afternoon with the information that Nessa had taken to her bed in a fit of the sulks, convinced that the P.W.’s appearance in the Park with two of the creatures on leads had been a direct insult to herself and her customary pair of little walking companions.

Viscount Stamforth, though a saturnine man of a naturally grim countenance, was entirely pleasant to themselves, but certainly gave no indication of why his wife had issued the invitation. They had arrived around midday on the Friday, for Stamforth town was not a very long drive from Brighton by the coast road, and then the castle was not so very far from that: not on the coast, but a little way inland: placed on the crown of a hill, with magnificent views over the Channel to the south and the rolling Sussex countryside in every other direction. Eudora was not displeased to be there; but—but why?

It would not be until the Sunday afternoon that any of the visitors would receive an explanation.

It was a warm, drowsy day, with the sweet scent of flowering honeysuckle in the air: the bees hummed in the enormous swag of it that overhung the great stone archway that was the entrance to the castle. The household had attended divine service in the morning at the local village church, for the Perpendicular chapel in the courtyard was no longer used. Though certainly in excellent repair, and the visitors had duly admired the gilding and the stained glass, as to the interior, and the flying buttresses as to the exterior. Rather small ones, but if Miss Gump and Miss Hewitt were in agreement that that was what they were, Eudora saw no reason to argue the point. Raffaella had at first called them something else, but it had been determined by the castle’s owner himself that this was merely the Italian for “flying buttresses”, so that was all right. There had been, Eudora was intrigued to see, a distinct twinkle in his eye at the time, though he had not smiled: so perhaps that was one reason why the P.W. had married him? It was, of course, perfectly clear why he had married her: and the fortune did not come into it.

Rather uncertainly Eudora admitted, on being questioned closely by the children, that she did ride, yes; and duly got herself into her habit and, escorted by Lord Stamforth himself—looking impossibly prim, so it was clear the damned fellow was trying not to laugh in her face—accompanied a crowd of small persons on ponies on an expedition to the house by the sea where—er—where the children had once spent a summer holiday? After quite some time it dawned on Eudora that that must have been the summer when Society had said that the P.W. had come down to Stamforth’s county express to capture him, and that it must therefore be that house. She could only hope that this thought was not writ plain on her face for Stamforth to see. Judging by the ironic look in his clever eye as he glanced her way, however, this was not a hope destined to be fulfilled.

The visitors had discovered to their astonishment that at home, not only was the P.W. entirely sans façon, she also did not bother with her dress: and normally got about the place in a succession of crumpled and rather faded cotton prints. Without a corset. At the moment she was increasing, though this fact was not as yet very evident, so possibly there was some excuse for her; but she certainly did not bother to drape her person in the modestly concealing wrappers and jackets which such as Susannah Quarmby-Vine and Raffaella’s own relatives would assume in those circumstances. Lady Stamforth had worn a very pretty silk of narrow green and white stripes to church in the morning, but for the midday meal had appeared reclad in a faded fawn print.

After the siesta to which she herself was apparently accustomed, and which Raffaella had confessed was her preference on very warm days like this, she appeared in the doorway of Raffaella’s room in the same faded garment. And asked her if she felt like coming up on the walls.

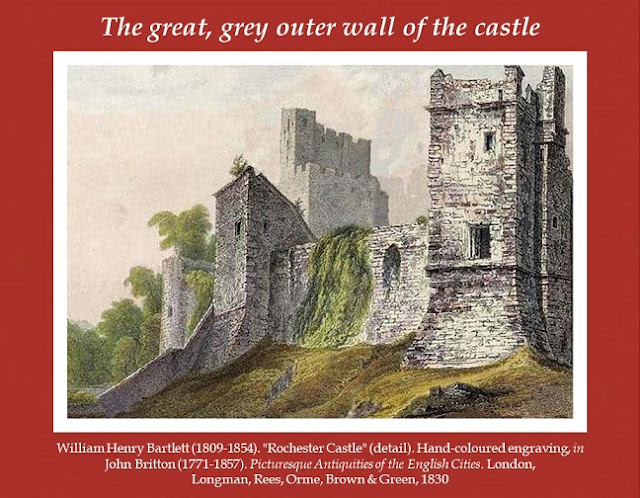

Raffaella was very glad to go up on the walls, so they mounted the steep series of steps which led up the great, grey outer wall of the castle to the view over the green-gold grassy prominence on which the ancient edifice was built, and thence over the little village and the farms, and out to sea.

“Eef one ees not short-sighted like me,” said her Ladyship, shading her eyes with her hand and peering; “one can just see the coast of France.”

Raffaella peered, but reported: “It is rather misty today.”

“The English Channel often ees,” agreed Lady Stamforth neutrally.

“Si,” said Raffaella on a sigh, leaning her arms on the warm stone and gazing out to sea.

Her Ladyship appearing also quite content just to lean and gaze, they leaned and gazed for quite a long time.

“Do you read French?” asked her Ladyship at last.

Raffaella jumped. “Er, yes, your Ladyship.”

“Good: I have a vairy naughty novel which I theenk you weell like!” she said in the soft, deep voice with the accent generally recognised by the gentlemen to be quite enchanting. And which Raffaella, though she had done her best to hate her, had ruefully recognised was. Lady Stamforth herself was very obviously one of those creatures endowed with a natural warmth and a quite natural charm, and not affected or vain, or—or anything which one had imagined! .And it was not fair at all: for she could be no more than a year or at the most two Raffaella’s elder, and yet she had everything: adorable children, a husband who adored her and had one of the oldest titles in England, an immense town house, jewels worth a king’s ransom, and a genuine Mediaeval castle to boot! True, Lord Stamforth did not in the least resemble a Black Warrior, being a lean, dark-visaged man in his mid-years with one of those chins which never looks particularly well shaven even when its owner’s man, an eccentric, one-eyed personality, has just informed his Lordship’s stunned visitors that it just has been; but he was clearly devoted to her, and very clearly understood her, and manifestly adored the children, even though none of them was his own, as yet, and— Well, he was not at all the type that Raffaella herself admired, but nevertheless she conceded that Lady Stamforth was a lucky woman. And all that talk about his “working it off” at the fencing salon was doubtless so much jealous nonsense, spread by all the silly fribbles who wished themselves in his place!

After a little more gazing out to sea the P.W. murmured: “I had a leetle note from Charles Quarmby-Vine. We are vairy fond of heem: he has been a kind friend.”

“Er—I am sure, your Ladyship,” replied Raffaella uncertainly.

“You weell probably not know, but when I first came to town, not everyone was vairy kind, for they all knew a horrid story about my mamma. Which was quite true,” she said cheerfully. “She was a Jeffreys—that ees Lord Keywes’s family—but that deed not mean she was ever a lady. She eloped weeth my Papa when he was steell married, and eet was only by the grace of God that I was even born een wedlock, for the poor Portuguese lady died just een time for Papa and Mamma to marry. When my next brother was vairy leetle Papa took us all out to India, but although he made hees fortune that deed not entirely answer, for Mamma ran away again: that time, weeth an Indian rajah. That ees like a prince. Though that aspect of her history was not so generally known een England; but you see, sufficient was. And some people suspected that she had never had the right to call herself the Senhora Baldaya at all, unteell my kind Uncle Érico Baldaya arrived een England and recognised us.”

At this point Raffaella believed herself to have seized her Ladyship’s intentions: she nodded, her lips compressed.

“But dear Charles was always vairy kind and never listened to a word of the horrid gossip,” she said, smiling at her.

Raffaella blinked. “What? Oh: Captain Quarmby-Vine. Um, yes,” she said uncertainly.

“And then, when I had blotted my copybook by— Well, eet ees rather complicated, and I do not weesh to bore you!” she said with her soft laugh. “Let me see: Lewis eenvolved heemself een a seelly duel—this was before we were married; indeed, before he had even proposed—and I tried to stop eet on the ground, and somehow the story got out. And though many people were vairy kind, some were not. Well: the high sticklers at Almack’s: you can imagine! But dear Charles was a staunch supporter.”

“I see,” said Raffaella weakly.

Lady Stamforth put a warm little hand on hers. “I should like to see heem happy. He ees a good man.”

“Yes,” said Raffaella, licking her lips. “I think he is. He has been very kind to me.”

“I am sure he has,” she agreed warmly. “Now, I theenk I shall act like an old married hag, yes? And ask you some personal questions to which you weell not weesh to respond. Well, firstly, do you theenk you could love Charles?”

Raffaella looked into the big dark eyes, and swallowed. “Um—no. Not in a romantic sense,” she said hoarsely.

“No, well, nor could I,” she said, nodding the tumbled brown curls that gleamed with gold lights in the sun. “He ees a vairy good man: vairy pleasant and kind. But you see, there ees much een my nature that ees neither pleasant nor kind. And though I thought I could be faithful to heem, I was not vairy sure that I could be always kind. And so I deed not take heem. Added to which, he ees the sort of man who ees only too ready to be a father to one, and though I am more than capable of playing the corresponding rôle, and indeed, deed so weeth my second husband, I do not truly need that sort of man: for me, it would always be only a rôle —you see?”

Raffaella’s jaw had sagged. No-one had ever spoken to her in this frank fashion in her life. In fact, until this instant she had had the strong impression that she herself was the only woman walking who even had such thoughts. “Yuh-yes!” she gasped.

“Lewis, you see, though more than capable of eet, refuses to be either a father or a mentor!” said the P.W. with that little gurgle of laughter. “Marriage ees much harder when one has to be a man’s equal, but een the end, much more satisfactory. Why, he even refuses to put me over his knee and beat me!” she said merrily.

Raffaella swallowed.

“Charles ees the sort of man who would do eet, when driven to eet: and I, alas, am the sort of woman who would deliberately drive the poor fellow to eet, just to see eef he would, you know? But then, he ees also the sort who would blame himself forever for having done eet, poor Charles. Whereas my second husband deed eet without a second thought!”

Raffaella nodded numbly. After quite some time she ventured: “Gianni did not truly care, I suppose.”

“The Conte dalla Rovere? I see. He was vairy young, I theenk? Yes,” she said as Raffaella gave a jerky nod. “Sometimes that works well, eef the two are young together and manage to grow up together, instead of growing apart. But when one of them ees not so vairy young, underneath, eet does not work, as far as my observation goes.”

“No. He was young all the way through. In fact, he was a blockhead,” said Raffaella, licking her lips.

“Then I do not theenk eet would ever have worked. You do not regret heem at all?”

“No, um, only at—at times,” said Raffaella, pinkening in spite of herself.

“So he was a good lover?” said her Ladyship in frank astonishment. “Usually the young ones are not.”

“No, well, he had already had a lot of practice, with older ladies.”

“Good,” said Lady Stamforth approvingly.

Raffaella’s dimples showed. “Mm!”

They looked at each other, and laughed a little.

“I cannot talk to Cousin Eudora about such things, although she is so very intelligent,” disclosed Raffaella abruptly.

“No, of course. Maiden ladies cannot understand. And many married ones, though they might understand, would affect not to,” she said with a shrug. “Well, sometimes eet ees vairy hard to hold out, when a pleasant man proposes, whatever eet might be that he proposes, when one suspects that he might be a pleasant lover, and when one knows how enjoyable that can be, yes?”

“Yes,” said Raffaella hoarsely. “We—we spent an afternoon in the Park, quite recently, with Katie Dewesbury and Commander Sir Arthur, when most people had already left town and—and it was very relaxed; and I could not help thinking, looking at the Captain, that—that he might be.”

The P.W.’s warm little hand squeezed hers. “Yes, of course.”

“But it would not be honourable to accept him, if I cannot love him,” said Raffaella in a low voice.

“Well, I suppose not, but pray do not expect me to play the rôle of mentor in this instance,” she murmured. Raffaella gave her a startled look; she made a wry little grimace and said: “Ees one human being ever fit to play that part, truly? A woman has to consider rather more than what ees honourable, when she considers linking her fate with a man’s.”

“I see,” she said slowly. “Yes, you are right.”

“He could certainly support your children een comfort.” She put her hand on her belly, and smiled a little.

“Yes,” said Raffaella, frowning over it. “That must be a consideration, certainly. I—I would do my best to make the Captain happy, if I accepted his offer. And he could offer material comforts and security, that is true. But— You are right: I would be playing a rôle.”

“Yes. And twenty years ees a vairy long time to play a rôle for which one ees not suited. You would be an old hag at the end of eet, and for what?” she said with a shrug.

Raffaella stared at her in horror. “You are right! Cousin Eudora attempted to intimate something of the sort, but… Even though there are many, many points in favour of it, I do not think I can do it.”

Lady Stamforth turned to lean her elbows on the old stone wall again, and gazed out at the misty horizon. “No, well, eet ees not easy to envisage the future. And of course one cannot foretell what weell happen.”

“No.” Raffaella also turned to gaze out to sea again. After a very long time she said in a low voice: “It could well be twenty years, or more: he is a healthy, vigorous man. Twenty years, married to a—a cheery blockhead whom one does not truly love? I can see myself breaking out and—and doing something disastrous,” she admitted.

“That was precisely my own thought: yes. Especially geeven my mother’s history,” admitted Lady Stamforth with a little shudder.

Raffaella nodded hard. Though adding: “I had thought I was not very like Mamma.”

“My dear, one does!” she said with feeling. “But then one day my next brother and I were quarrelling, and he accused me of being just like her: and to my horror, I saw that een many ways, I am! Well, the whole town weell tell you I enjoy the company of gentlemen far too much, and eet ees perfectly true,” she said detachedly.

Raffaella nodded dazedly.

They leaned on the wall, and gazed at the sea…

After some time the P.W. said baldly: “Uncle Érico ees seventy-nine years of age.”

Raffaella gulped.

“In spite of hees bulk, he does not geeve quite that impression, I theenk?” she murmured. “But he ees: I have checked eet with my cousin Mauro. He has always been vairy careful of hees health, een spite of the indulgence in sweetmeats!”

“Yes. Those pink ones you sent were lovely,” said Raffaella dazedly. “I thought he was about sixty-five.”

“No,” she said simply.

Raffaella swallowed hard. “I do not know if you are aware of this, your Ladyship, but he has offered marriage.”

“Yes. He ees like all the Baldayas: vairy self-aware, a leetle self-indulgent, and vairy, vairy cunning,” she said tranquilly. “Even my leetle brother, Dicky, has eet: though Weenchester ees doing eets best to get heem out of eet!”

The grinning, brown-haired urchin who was Master Baldaya had not struck Raffaella particularly at all. She blinked. “Oh—your little brother is at Winchester? I see. Um—yes, I accused the General of being more or less that,” she admitted, swallowing.

“I know: he was most tickled by eet,” she said calmly.

Raffaella’s face flamed.

“Well, yes, he has told me everything, for he knows our minds are alike and vairy leetle he could say would shock me,” she said calmly. “We have become the fastest friends. Initially I made the meestake of taking heem at face-value!” she said with her gurgling laugh.

Raffaella smiled a little. “Oops.”

“Eendeed! He would make you happy for a few years, you know, and leave you comfortably well off at the end of eet,” she said matter-of-factly.

“Mm,” she agreed, chewing her lip. “I—I do like him.”

“But his person ees so gross? Yes. I admeet that ees a drawback, but then, on the other hand he knows vairy much about women. Being een his bed would not be entirely unpleasant. And of course he ees scrupulously clean een hees person. That ees a verbena scent, weeth a hint of attar of roses, that he uses: I like eet vairy much, do you?”

Raffaella gulped, but nodded gamely.

“But then,” said her Ladyship, leaning her dimpled elbows on the old grey stone and staring at the horizon with a frown and a sigh: “I grew up in a vairy hot climate, full of vairy spicy and delicious smells.”

After a moment Raffaella said sympathetically: “I see. You miss India, do you?”

“Tairribly,” she said with another sigh. “When I am expecting a baby eet ees always worse, I find: my body seems to demand to eat theengs eet cannot have, for although my women do their best, one cannot get all the vegetables and fruits here, and the sweetmeats and peeckles they produce are never quite the same. Oh, well. I would never tell Lewis how homesick I am sometimes, for eet would upset heem, and there ees nothing to be done about eet. But sometimes I hate England.”

Raffaella looked at her very sympathetically but could think of nothing to say.

“That,” said her Ladyship on a guilty note, “was not meant to be some sort of a plea for you to consider Portugal with Uncle Érico.”

“No, of course, your Ladyship,” agreed Raffaella.

She turned her head, and sighed impatiently. “Call me Nan. The English prunes and prisms annoy me. Though all cultures have their social forms, out of course.”

Raffaella nodded dazedly. “Yes. Thank you, Nan, I should like to very much.”

“Ees there anyone else who might offer, Raffaella?” she demanded abruptly.

“No,” said Raffaella honestly. “Not marriage. H.-L. made a dishonourable offer.”

“Really? I would not have said he had the bottle. Well, he ees a pretty boy but unless you are madly een love weeth heem, I would say eet ees not to be considered.”

“No, well, I did refuse: I am not in love with him at all, Nan!” admitted Raffaella with a smile.

“That ees just as well.”

“I don’t know… In a way, a grand passion must make the decision easier.”

“I have often thought that,” agreed the P.W. detachedly.

The two ladies leaned on the wall, gazing out to sea.

Eventually Raffaella said: “Thank you very much for broaching the subject, Nan.”

“No, well, I did not theenk any of your stuffy B.-D. relatives would, kind though they have been: for they strike me as vairy like my kind Jeffreys relatives. And as I am vairy fond of both Charles Q.-V. and Uncle Érico, I thought I had best do eet.”

“Mm.” Raffaella eyed her dubiously. After a moment she said: “May I ask, Nan, if you consulted first with Lord Stamforth?”

“Weeth Lewis? No!” she said with a choke of laughter. “He ees not my mentor! No, well,” she said, twinkling at her: “he has guessed, of course: that ees why he has let the children drag poor Miss Bon-Dutton off for a ride this afternoon.”

“I see. You are very lucky," said Raffaella frankly.

“Yes. But I married my first husband when I was barely turned seventeen, and when he died when baby Johnny was but one year old, I deed not theenk so. And eet was much, much worse after I found dear Hugo and he was keelled in that hunting accident before we had been married two years.” She sniffed suddenly and passed the back of her hand across her eyes.

“I am so sorry!” gasped Raffaella.

“No, do not be: I become grossly sentimental when I am increasing,” said the P.W. calmly. “Eef eet had not all happened, I would never have found Lewis.”

“Mm: one never knows.” said Raffaella slowly.

“Well, I was not citing eet as an object lesson!” she said, smiling at her. “Shall we go and play weeth Rosebud? She ees so meeffed when the older ones go riding weethout her, but she ees too leetle to go vairy far on her pony.”

Miss Rosebud Benedict was, at Raffaella’s calculation, about three years of age. She smiled at her mother and said: “I should love to play with her, Nan! And can she truly ride her pony?

The P.W. took her arm. “Yes; eet ees a vairy leetle one. I have forgot what Lewis calls eet. Something Scotch?”

“Um… Oh! A Shetland pony?”

“Yes, that’s eet. She sits on eet vairy nicely, for Lewis put her on a horse before she could walk. She has called eet Spotty because eet ees somewhat dappled; and the other children have been vairy rude about eet, claiming that only a dog may be called Spotty een English. So all een all, I think she deserves some spoiling, no?”

Raffaella agreed, and the two young matrons repaired to Miss Rosebud’s big, airy nursery, rescued her from Nurse, and took her out to play on the green-gold, closely mown sward of the sunny slope before the castle.

It was, as Lord Stamforth remarked on finding them there, the three curly heads wreathed with honeysuckle, the grass now strewn with rugs, parasols, and toys, and the remains of what had clearly been an Indian feast, an idyllic sight.

“She gave me,” reported Raffaella, as Eudora was changing for dinner, “some good—well, I suppose you could call it good advice.”

Miss Bon-Dutton eyed her dubiously. “The P.W.?”

“I absolutely forbid you to call her that!” said Raffaella with a laugh. “She is the warmest-hearted thing; but so intelligent with it!”

“Tell me that that is what Wellington sees in her if you dare.”

“I would say that is very much not what he sees in her, and we are not talking about him. It was not precisely advice, but it was good!”

“Oh.”

“And the conclusion I have come to, or very nearly come to,” said Raffaella with a little frown, “and which, remark, I am very nearly almost sure is what she intended, the cunning thing, is that it would be utterly unfair both to Captain Quarmby-Vine and myself to accept his very kind offer.”

Eudora’s jaw dropped.

“Yes, see? She did not invite us for the purpose of warning me off her uncle, at all!”

“I admit that was the thought that sprang to mind,” she croaked.

“Yes, well, on the contrary. The General is seventy-nine, and the suggestion she wished to convey was that a few years with him would not be as unpleasant as the grossness of his person might suggest. Added to which, as she very clearly indicated, it is only the bulk that is gross: the actual person is scrupulously clean and deliciously scented!” she said with a choke of laughter.

“Even the P.W. cannot have said that!” she croaked.

“But certainly; in almost those exact words.”

“You mean she wants you to marry the old creature?” said Eudora faintly.

“Apparently, yes. Certainly she wants that more than she wants me to make Captain Q.-V. unhappy.”

“Did she imply you would?”

“No, she is not so unkind. But she did point out that after twenty years of an incompatible marriage I would find myself a hag with nothing to show for it. No, well, on thinking it over,” said Raffaella, wrinkling her brow, “first she allowed me to make the point that it would not be particularly honourable to accept the Captain if I cannot love him. After that she pointed out the advantages of taking the General.”

“And the fact that he is seventy-nine?”

“Yes,” she said serenely.

“Did you ask if the males of the Baldaya family commonly last into their nineties?” said Eudora grimly.

“No. She said nothing outright but the implication was that it is not anticipated.”

Eudora groped her way to her dressing-table and sank onto the chair before it. “Raffaella, does this mean that you are seriously considering the General’s offer?”

“Yes; though I have not nearly made up my mind, yet. Um, she did make the point, which I had already discovered for myself, that General Baldaya is very clever. –Not a tactician, of course,” she said with a little smile.

“You mean to stand there and tell me that you actually like him?” she croaked.

“Yes. So does Nan.” Raffaella went over to the door. “Wear something grand this evening, Cousin: they are expecting him for dinner; and a Sir Jeremy and Lady Foote from a nearby property, and Admiral Dauntry and several other swells.” She wrinkled her little straight nose at her, and went out.

Miss Bon-Dutton sat there numbly. After quite some time she put a hand to her head and muttered under her breath: “The P.W. is become ‘Nan’, and one is not to use the initialism in the future? Am I going mad, or is the world around me doing so?” After quite some further time she took a deep breath. “Well, if the P.— Pardon me, if Lady S. takes her up, her future must be supposed to be safe enough. But in her shoes, if it was a choice between a gross, scented old thing of seventy-nine and Charles Q.-V.—?”

But try as she would, Miss Bon-Dutton could not truly envisage herself in that situation. Well, poor little Raffaella. She would let her get over the influence of the P.W.’s persuasiveness and charm—which there could be no doubt the creature had used on the girl this afternoon—and then repeat the point that it was not merely a choice between those two gentlemen, and that Raffaella must consider she had a home with herself for as long as she would need it.

And with this she took a deep breath, rang for her faithful Janet, and intimated that the blue silk would not do, it had best be something “grander”.

It did not occur to Miss Bon-Dutton that to a woman of Raffaella’s type—and, indeed, of Nan Baldaya Vane’s type—the prospect of living with her spinsterish self for an indefinite period might strike as a great deal less attractive than marriage with a well-off gentleman, of whatever age, who was fully prepared to doat on her.

Next chapter:

https://raffaella-aregencynovel.blogspot.com/2022/11/an-unromantic-decision.html

No comments:

Post a Comment