7

The Cauldron Simmers

It was not long at all before that which vigilance which Miss Bon-Dutton had vowed should be her watchword was called upon. Somehow or another a concert with a Mrs Paxton, who was Major Fellowes’ sister, led on insensibly to a little supper party at the house of that Lady Caro Kellaway who was Gwennie Lacey’s sister-in-law.

Lady Caro was a thin-faced, discontented-looking young woman; not dark like her little sister Laetitia and the Lacey side of the family, but fair, like her mother. She was not as pretty as the Duchess of Munn in her youth had been, and had, indeed, in spite of the Lacey name, done very well for herself in capturing Simon Kellaway, a gentleman somewhat older than herself who was generally held to be well on the way to a most distinguished diplomatic career. Since marrying him Caro had become very fashionable, was reliably reported to be spending a fortune on dress, and had taken up faro, at which she was reputed to have very little luck. She had a little set of her own, composed largely of like-minded young women and the fribbles who generally hang around such young women.

Her Ladyship’s pretty little house just off Green Street featured a salon done out in very modern taste: straw-coloured hangings, several elegant low sofas, a chaise longue or two, and a scattering of Egyptian artefacts which one must conclude Simon Kellaway had picked up in his travels—that type of thing. Supper featured Lord Geddings sitting very close to the Contessa dalla Rovere on one of the elegant sofas and gaining the information that actually, they did sometimes ride in the Park in the mornings: yes. Under the resentful eyes of their hostess; ouch. So Eudora was relieved rather than otherwise when it speedily appeared that the object of the gathering was not merely supper but cards.

An adjoining room opened for the cards proved to feature rather a lot of black lacquer, including a set of chairs with ormolu lions’ feet that, really, would not have disgraced the court of the Empress Josephine. Eudora herself would not have given it house-room but she admitted silently that Lady Caro had certainly managed to display it to its best advantage: it was set off by more of the straw-coloured satin and one or two touches—a couple of bowls, the odd footstool and so forth—in a striking deep turquoise shade.

Caro Kellaway shrugged in her discontented way on Raffaella’s exclaiming admiringly over it. “Oh, well, thank you, Contessa. The Egyptian look is really quite outmoded, you know, but Simon insisted we keep these pieces. But the little cat is quite charming, I am quite fond of it. –That,” she said with a nasty look at a porcelain Chinese lion, “is allowed to stay in here only because its colour tones with the other blues. I cannot imagine why Simon did not bring back something prettier from his expedition to China; all the other gentlemen did!”

“This pair of fine lacquer cabinets are, I think, Chinese work, too,” murmured Eudora.

Lady Caro gave them an impatient look, shrugged, and said: “I dare say. Now, do you care for faro, Miss Bon-Dutton? Geddings has consented to take the bank tonight.”

Eudora was sure he had. Lord Geddings was known for his predilection for gaming. And for the ladies. “Thank you, but the Contessa and I should prefer to play at lottery tickets with the girls.”

“Oh, well, in that case, I am sure I may trust you to keep your eye on Letty also!” she decided with patent relief.

Eudora had seen that coming: she merely bowed slightly and suffered herself to be led off to lottery tickets.

The Contessa, however, though she did it without argument of any sort, had decided against lottery tickets. That gallant hussar, Captain Paxton, had volunteered to teach her piquet. Eudora was aware that Raffaella was very fond of piquet and, in fact, beat her, Eudora, hollow every time they played. She eyed the pair drily but merely said: “Of course, if you wish for it.” And sat down resignedly to lottery tickets with the young people—though keeping her eye prudently on the pair. After some time they were joined by a Lieutenant Rupert Gratton-Gordon, also of the hussars, who apparently persuaded them into a game of écarté. Eudora broke it up when it was getting to the shrieking and wrist-slapping stage and bore her trying charge inexorably away.

“I should rather have liked to have played faro,” Raffaella noted wistfully in the carriage.

“Unsuitable for a young widow,” said Eudora, yawning. “Especially with Geddings.”

“Why, he is a friend of the Duke of Wellington!” protested Raffaella primly.

“That does not make him fit company for young women.”

Raffaella’s eyes twinkled. She said in a demure voice: “Lady Caro was playing, and she is both young and a duke’s daughter.”

“I would not say he is fit company for her, either.” She yawned again. “I do beg your pardon.”

“Were you dreadfully bored, Cousin Eudora?” asked Raffaella, biting her lip.

“Sufficiently. Lady Caro’s friends are a pack of empty-heads.” Eudora hesitated and then did not express her other thought, which was that, duke’s daughter or no, Lady Caro lived somewhat on the fringes of Society, and it could do Raffaella very little good to be seen with her set.

“Well, we must start our own salon very soon!” she said brightly.

Eudora swallowed. “Mm.”

“What a surprise,” said the Contessa dulcetly, as Geddings swept off his hat and bowed very low from the back of a glossy black gelding.

His Lordship’s eyes sparkled. “Surely you cannot have forgotten that we agreed we might meet in the Park this morning?”

“Oh, was that you?” replied Raffaella in mild surprise.

“Good morning, Lord Geddings,” intervened Eudora evenly.

Geddings gave her a brazen smile and greeted her politely. Not omitting to add that she was looking very fetching today.

They rode on together, perforce. The fact that Geddings must be fifteen years Raffaella’s senior did not prevent his flirting outrageously with her…

Eudora was actually glad when Captain Quarmby-Vine hove into view in the company of Commodore Gatenby and Commander Sir Arthur Jerningham. Though not particularly glad to hear Raffaella go into positive trills of laughter as his Lordship murmured something about a “flotilla.”

She played Geddings, poor old Charles and the Commodore off magnificently against one another. Gatenby, who was not of course in the least serious, appeared to enjoy every moment of it. The same could not have been said of Captain Quarmby-Vine, and in fact Commander Sir Arthur, who was riding politely along beside Eudora, was after a while heard to mutter under his breath: “Poor devil.”

“Well, yes. Though you cannot say he does not ask for it,” she murmured.

“He’s a decent fellow: surely she can see—” He broke off, frowning.

“I am sure she can. It does not entirely count, with her; and I have to admit that she is not, really, any more interested in poor Charles than she is in either of those other two fools.”

“No.” He frowned. “Miss Bon-Dutton, I think you should be aware that, though Gatenby is harmless, Geddings—er, well, let us just say, is known as something of a lady-killer.”

Say, rather, the town was littered with his mistresses, past and present! True, all somewhat older than Raffaella. He would most certainly not have seduced a débutante—but then, Raffaella was not a débutante, was she? “I am aware of that, but thank you for reminding me, Commander. I shall take care. But I don’t think it’s within human capacity to stop her flirting with any of them,” she ended on a wry note.

“Er—no.” He hesitated. “Well, pretty little creature: very fetching. And very young, of course; no harm in her. Knew Jeremy Andrews quite well, y’know: a decent fellow. Er—dashed pity about the mother.”

Eudora gave him a not unkindly look. “Quite.”

They rode on in silence for a while. Ahead of them, Raffaella’s gurgling laugh sounded very often.

The Commander took a deep breath. “Look, it’s none of my business, but— Er, well, I think you must be aware that there is an unkind story going around about your little cousin.”

“Yes, I am aware of that. I shall not scruple to tell you, Commander, that there is considerable bad feeling between Raffaella and her mother and that the stepfather is a corrupt monster.” Eudora’s lips tightened angrily, and her eyes flashed.

Commander Sir Arthur did not, of course, admire such women in general, but he thought involuntarily what a magnificent creature she was, after all. “Aye, know that. Um, look, perhaps your sister Lilian has told you this, ma’am: Bobby Quarmby-Vine had the true story from young Jack Beresford a month or so back: he had it from his brother-in-law, Keywes, this last Christmas: they are back in England, you know. The Conte dell’Aversano tells a very different version from the one the clubs have hold of. There seems no doubt the girl was the victim in the affair, poor little soul.”

“Yes,” said Eudora, smiling at him, and having to blink, rather. “She was, indeed.”

“Aye.” Commander Sir Arthur cleared his throat. “The thing is, ma’am, that that won’t necessarily be the version that the world believes.”

“No-o,” said Eudora slowly. “I did know Lord and Lady Keywes had returned from Rome. Did Mr Beresford spend Christmas at Vaudequays with them, then?”

“Aye, that’s it.”

“And he—Mr Beresford—believes the true story?”

“Young Jack? Oh, aye. No question. Quite steamed up about it, actually.” He glanced sideways at her. “Forgive me, but I would not encourage the little Contessa to hold out any hopes in that direction. Her innocence in regard to this particular affair would not render the family acceptable to the Beresfords, I am afraid.”

“We have not seen him: I do not think he is in town. But I shall not encourage her,” said Eudora with a sigh. They rode on in silence again. Eudora then found she was explaining that they would be at home on Tuesdays and if the Commander should care to look in, very glad to see him. He smiled his pleasant smile, and promised to call. Eudora was not quite sure whether it was just his good manners or the hope that Katie Dewesbury might be present. Should she urge him to tell Katie that he now believed Raffaella innocent in the elopement scandal? Er—it was difficult to see how, without giving offence, or the impression that Katie had been gossiping about the man behind his back… Bother. Well, if he came to their Tuesdays, and Katie also came, perhaps Nature would take care of the rest.

Commander Sir Arthur, for his part, was left with the feeling that Eudora Bon-Dutton was, as well as a fine figure of woman, a very decent sort indeed, and that it was a damned pity that poor old Charles could not have fixed his interest there, instead of hanging on the sleeve of a pretty little flirt of half his age. But he did not speak to Charles on the subject: he was aware that in matters of the heart talking paid no toll.

“We have given this gown,” explained Raffaella smugly, “a new touch. It will be just the thing for the opera!”

Eudora nodded numbly. It was that damned emerald satin of hers. Raffaella, doubtless with Jane’s help, had removed large portions of it, and was wearing it as an underdress. The gown over it was a fine gauze: black. Its filmy unlined puffs of sleeves were adorned by small bows of the satin, and it featured one ruffle at the hem, in which nestled more tiny bows of the emerald. The effect was quite exquisite but not entirely suited to a very young widow. In fact, being entirely suited to drawing all eyes towards the young widow, it fell well within the category of dashing.

“Dashing,” produced Eudora limply.

“Worthy of the P.W.?” she said hopefully.

Given that the P.W. had exquisite taste, though possibly not in the matter of actual necklines, no, but given that otherwise she had exquisite taste and a nabob’s fortune to support it… “Very nearly. She—er—she is not precisely dashing, but I do not know that my poor tongue can describe the effect.”

“Oh. Not precisely dashing… So, is she unexceptionable?”

Eudora raised an eyebrow. “That depends to some extent on your political leanings and your feelings towards the Portuguese.”

Raffaella smiled. “No! Not as an acquaintance, dear Cousin; as to her style of dress! But I shall not persist: I quite see that ‘not precisely dashing’ was your best effort!” she admitted with a gurgle. “—I thought the Portuguese were quite in favour, in England?”

“I think that depends on one’s political leanings, also? No, well, certainly she is old Érico Baldaya’s niece, but on the other hand, Stamforth is not in great favour at the Portuguese Embassy. One is reliably informed they will be at the opera tonight—though not in Wellington’s company,” she noted drily; “so you will be enabled to see her in person, at last.”

“Huzza! But why not in Wellington’s company? Is she not his type?”

Eudora gave her a dry look. “Au contraire.”

“I see! You mean the husband don’t encourage it?”

“I do not mean precisely that. Though it is fair to say he does not.”

Raffaella rolled her eyes wildly.

“Stamforth and Wellington have never seen eye to eye politically. Added to which,” said Eudora, taking a deep breath, “he, that is, Stamforth, supported Sir John Stevens’s recent stand against the Prime Minister. It was reported in the morning paper, you may remember. The ill-feeling between Stamforth and Wellington goes back to Peninsula days.”

Raffaella and Miss Hewitt both nodded interestedly, and, Mr Freddy Bon-Dutton then being announced, they were enabled to go into dinner discussing the somewhat involved history of the Stamforths, His Grace, and the Portuguese.

… “There,” murmured Eudora, as they settled themselves in their box that evening. “The P.W.”

The Contessa stared at what was presumably Viscount Stamforth’s box. It held a slim, saturnine gentleman, a stout, complacent-looking man in a green waistcoat, a very pretty dark-haired lady in shimmering silvery lilac, and approximately fourteen fribbles in dress uniform.

“The thin, dark man is Stamforth, and the stout person on her Ladyship’s other side is his cousin, Mr Tobias Vane.”

“Quite a warm man,” said Mr Freddy, shaking his head. “Not interested in anything but tea and receets, though. Well, and his cousin’s wife, y’see, but purely platonically. He is a bachelor, but frankly, don’t think I’d waste me efforts, if I were you, Contessa.”

Raffaella peered. “I cannot see a thing but fribbles in dress unif— Ooh!” she gulped, as one of them turned its head and revealed itself as Captain Quarmby-Vine.

“It will be interesting to see at whose shrine he ends the evening,” said Eudora drily as he caught sight of them, and smiled and bowed eagerly.

“Si!” she owned with a giggle. “Would you say that that gown is lilac or silver?”

“It is the palest, most silvery lilac imaginable, my dear Raffaella, and I am astonished you should not instantly have recognised it as such! Some claim any lilac will make a woman of that complexion appear sallow, but I am not capable of such happy self-deception. No, well, it is a shade she often wears. Tonight merely with her diamonds, not the famous black pearls.”

Raffaella nodded numbly. Lady Stamforth’s neck and arms were ablaze with blue-white fire. “Is he fabulously wealthy or does he not care what she spends?”

“I do not know if he cares what she spends, but were I forced to cast my vote I should have to admit that, possibly alone of all England, I believe he does. –No,” she said with a laugh as Freddy choked, and Miss Hewitt emitted a strangled titter, “she brought him two fortunes from her previous husbands, my dear. Well—er—do you see? That is her style.”

Raffaella sighed. “I do see, yes. I would look as yellow as a Chinee in anything even approaching silvery lilac. But I suppose one can summarise her style as gowns of exquisite cut, almost unadorned, combined with fabulous jewels.”

“Puts it dashed well,” agreed Freddy mildly.

“Please, tell me who some more of the notables are, before I cut my throat!” begged Raffaella with a gurgle.

The Bon-Duttons obliged. When Raffaella indicated a box containing an elegant fair woman in what appeared from this distance to be white lace over pale green silk, Eudora hesitated.

“That’s the Fürstin von Maltzahn-Dressen,” said the innocent Freddy helpfully.

“Oh, a German?”

Unaware that his cousin was cringing where she sat, Mr Freddy explained happily: “Not at all, Contessa. She was a Miss Beresford, and was generally reckoned to have made the catch of the Season—in her day, y’know, which was not yesterday. Though she is known to be wonderfully well preserved.”

“I see,” said Raffaella tightly. “I think I have heard the name.”

“Oh, you would have, aye: very fashionable indeed. Lives in London now, y’know: been a widow for some years. Pleasant house near the Park. The little red-headed creature’s her daughter: the Princess Adélaïde. Bit freckled, face like a pug. Don’t take after the mother at all, unfortunately. Nor the father, neither. Not that he were the father, come to think of it. Well, dead spit for damned Fritzl, ain’t she?” he said to his cousin.

“Yes. The florid man in the box is Hans von Boltenstern, an attaché at the Prussian Embassy, Raffaella, and—er—you know Lord Geddings,” finished Eudora faintly, as Geddings, who had been leaning against the railing of the box with his back to them, turned his head.

“So ’tis,” discerned Freddy. “Well, Contessa, if Geddings is with them,” he explained kindly, “presumably the rumour that they have a Wellesley sprig in mind for the little Princess cannot be discounted. Geddings is known to be Wellington’s mouth-piece. The fellow what they had lined up for her popped off a while back: Austrian princeling, or some such. Ma B. will probably try to throw poor Jack Beresford in her path this Season, if she’s on form, but I don’t think the Fürstin will stand for that one. Well—first cousins, for one thing. And then, Jack B.’s not a pauper by any means, but with the von Maltzahn-Dressen connection, they can do better for her. Though mind you, she has been hanging fire for a year or so.”

“Quite,” agreed Eudora limply, as the Contessa merely nodded brightly, though with a grim look round her mouth. “My dear, pray do not st— ” She broke off. Too late: Geddings had observed Raffaella looking at his party across the width of the opera house and had raised his quizzing glass. He smiled, and bowed. The Fürstin was then observed to beckon to him. They conferred. Fanny Beresford von Maltzahn-Dressen raised her lorgnette. Ugh. After a moment or two she bowed very slightly to Eudora. Limply Eudora bowed back.

“Dashed high stickler, y’see,” explained the helpful Mr Bon-Dutton.

“Oh, sicuro!” returned the Contessa airily. “In that case, we shall not expect cards, shall we, Cousin Eudora?”

“No,” said Eudora faintly.

Raffaella tossed her head defiantly. “Well, at least it was not the cut direct! And you look entirely womanly in that dove-grey silk. I dare say Captain Quarmby-Vine will be here at any minute to tell you so!”

“Aye,” said Freddy kindly. “The russet velvet ribbons are an unusual touch, Cous’.”

Eudora swallowed a sigh, but responded: “You do not think I have gone too far? Russet velvet with grey silk does not strike as odd?”

“No, no: charmin’!” said Freddy with his pleasant smile.

“There, my dear Miss Bon-Dutton: what did I tell you?” said Miss Hewitt pleasedly. “We had purchased ells of the ribbon in a desperate attempt to find something to go with that unusual necklace of dark amber beads: I have never seen another quite like it. Most amber is far more yellow. And then, you see, Mr Frederick, your cousin’s maid thought of combining it with the dove-grey!”

“And when the freesias were delivered, of course we saw that the were just the thing,” continued the Contessa eagerly; “and though she did not feel she could carry a posy, like a young girl, we thought they would look quite unexceptionable on the bosom!”

Gallantly Mr Bon-Dutton agreed they looked charming on the bosom.

“And,” said Raffaella with a twinkle, “only guess who sent them!”

“It was a courtesy, only,” said Eudora limply. “He knew my father.”

Ignoring this completely, Raffaella explained: “It was Mr Hugh Throgmorton. I am sure you know they are connected to positively everybody, and in especial he is the Marquis of Rockingham’s maternal uncle, of course! And we were told that it was his nephew to whom the Laceys were trying to marry off Lady Letty!”

“Oh, Lord, yes: Tommy Throgmorton. Fellow what ran off with a farmer’s daughter. Yes, well, old Hugh would have known Uncle Harold B.-D., all right and tight.”

“He is over seventy, and has been a widower for nigh on forty years,” said Eudora heavily. “There: that is he, opposite.”

Raffaella looked with interest at an elegant old man sitting alone in a box opposite theirs, explaining by the by: “She does not wish to become a comforter to him in his old age. Oh, but Cousin, he is such an elegant old creature! I do not think you would find the position onerous!”

“Aye, that’s right,” agreed Freddy, trying not to laugh. “Added to which, Wenderholme, you know!”

“What is that?” responded the Contessa.

“That’s his house, Contessa. A delightful Adam manor. Small, y’know, but the most delightful proportions.”

“Yes, well, any lady might be excused for wishing to become the mistress of so perfect a house,” said Eudora with a little sigh. “But I refuse to marry old Hugh for his house. Added to which, he has not offered,” she noted drily.

Their box was laughing over this sally, when two men, one very young, were seen to join the elderly gentleman in his box. And Miss Bon-Dutton might have been seen to wince.

Not noticing this last, the helpful Mr Bon-Dutton explained happily: “Talkin’ of perfect Adam manor houses, that tall fellow is Sir John Stevens, and I believe he does own a delightful house which is after the style of Adam. Never seen it, meself. Well—humbug country, y’see. Not sure who the boy is.”

Grimly Eudora returned: “We can tell you that. His nephew. A Mr Jerry Brantwell.”

“We encountered him a bookshop, and he is become quite a friend,” said Raffaella airily. “He is… bother, I have forgot the word.”

“An imbecile?” offered Eudora blightingly.

“No!” she choked, going into a trill of laughter. “You know: when the Dean has said one has been very naughty and must go home until the next term!” she said to Mr Bon-Dutton.

“Oh! Rusticating,” he said with a grin. “Hullo, here’s another. No, two.”

“Uniforms!” discerned the Contessa pleasedly.

“Aye. The younger is a Colonel Calhoun, he is a friend of Stevens’s, I believe, and the older is General Sir Mortimer Sinclair. He and Hugh Throgmorton are old friends.”

Raffaella looked at the box critically. “The general is old and fat: we can dismiss him! The other is not entirely unpleasing to the eye. –Help! Who is that?” she gasped as a fat, florid and immensely ornate figure entered Mr Throgmorton’s box. “Ooh, is it York?” she hissed.

“No. That is General Baldaya, the P.W.’s uncle. Though I should warn you, his reaction to our quizzing his box will probably be very like York’s,” warned Eudora at her driest.

“Bound to be. Dashed loose scr— Um, not a fellow what it would do to encourage, Contessa,” Mr Freddy corrected himself somewhat lamely.

“I see!” she said sunnily. “Should I wave to little Jerry B., do you think?”

Eudora replied grimly: “I think you must know the answer to that,” and Raffaella, though looking naughty, merely directed an arch look over her fan at the hapless Mr Jerry.

“Chalk and cheese, old Baldaya and Stevens, hey?” said Freddy to his cousin. “T’only reason he is with Sir John, y’see, Contessa, must be that the Portuguese are trying to persuade the government to send him out again.”

“That is certainly possible. –That they are trying to do so. Not that he will be sent,” replied Eudora in a hard voice.

“But explain!” demanded Raffaella.

“Oh—Sir John was out there—well, it must have been some time between ’06 and ’12. A liaison position. Unofficially, I think in order to soothe any feathers Wellington’s—er—matter-of-factness might have ruffled. Before that he was in India,” ended Eudora in a vague voice, staring blankly at the chattering throng.

Raffaella gave her a sharp look. “Oh? It is certainly wheels within wheels, is it not? Not to say, connections of connections. Was not the P.W. at one stage in India?”

“Mm? Yes, her first husband was a nabob. Er, no, there is no connection!” said Eudora, coming to herself with a jump. “She would have been the merest infant at the time, I think she is not so very much older than you. Er—no, I just— Well, Stevens did not take his wife out to India, it was at the period when our ships still had to run the French and Spanish blockades off the Iberian Peninsula: about ’04, I suppose. She died while he was out there: very sad.”

“I see.” She looked with interest at the coldly handsome profile in old Mr Throgmorton’s box. “So, he has been a widower for—what? Nigh on twenty years?”

“Possibly not that much, he was in India for several years. But more than fifteen, I think.”

“Mm,” she murmured. What a great pity they had got off on the wrong foot with Sir John! As an eminent Tory widower in need of a political hostess he would be the very thing for Eudora! Raffaella was mediating whether it might be possible to mend their fences with him when the door to their box opened and a hearty male voice said: “Well, now! Is not this something like? All together again, just like those delightful times down at Sommerton Grange!” And in the blink of an eye Captain Quarmby-Vine had seated himself very close. Though he explained regretfully he must not stay long.

“You are positively naughty, sir,” Raffaella reproved him, looking impossibly prim, “for the minute I take my eye off you, you go off to lay yourself at another lady’s feet!”

The Captain was not in the least put out by this reproach and responded instantly, looking as soulful as was possible for a florid man of a cheerful temperament: “The thing would be, Contessa, not to let a poor fellow out from under your eye, y’see.”

She gave a delighted trill of laughter and smacked his arm lightly with her fan.

Miss Bon-Dutton at this point might have been heard to swallow a sigh. “Tell us about the piece, Captain,” urged Miss Hewitt hurriedly. “What is being said of it, have you heard?”

Obligingly he reported what he had heard. As he had apparently heard it from the Marquis of Rockingham, Miss Hewitt evinced breathless interest, and the conversation became more or less general until the conductor entered to a scattering of polite applause and the Captain, with a flowery speech of regret and faithful promises to return, took himself off.

Eudora stared at the stage, seeing nothing and hearing very little. If only it had not been— No, well, that was absurd: John Stevens or another. There were sufficient stiff-rumped fathers and uncles in London for Raffaella to have been bound to run foul of at least one before long.

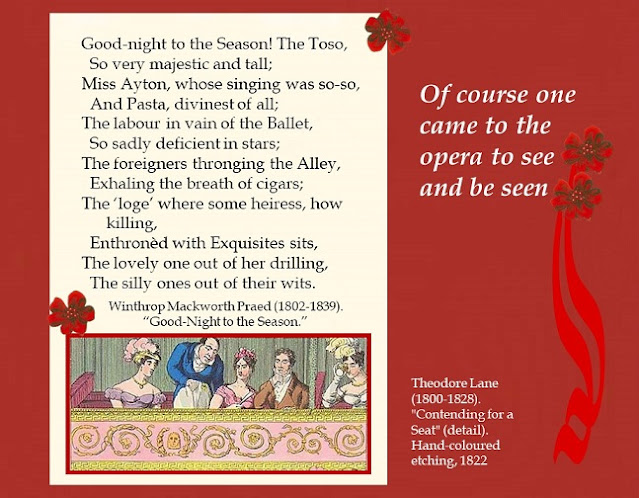

Of course one came to the opera to see and be seen, and their box did not by any means pass unnoticed by the crowd of fashionables at the opera house that evening.

“Who is that perfectly lovely little creature opposite?” asked Colonel Calhoun in the first interval.

The florid General Baldaya peered. “Exquise!” he approved.

“En effet. Somewhat after the style of your niece, Lady Stamforth,” agreed old Mr Throgmorton politely. “I do not know her, but I believe she is a guest of Miss Bon-Dutton. The Contessa dalla Rovere. Formerly a Miss Andrews.”

“Ah? Sir Peter Andrews’s family?” The General had a wide knowledge of the personalities of English Society, not to say of Continental Society; there were some, indeed, who had been known to claim that he had the entire Almanach de Gotha in his head. And very little else, save the steps of all the fashionable dances. Wellington at the height of the Peninsula conflict had been heard by the privileged few to claim something very much ruder in this regard, but then, His Grace and General Érico Baldaya had ever been chalk and cheese.

“I believe not,” replied Mr Throgmorton neutrally.

The General took another look. His already protuberant eyes bulged. He uttered an exclamation in Portuguese. “The daughter of the frightful Principessa Claudia! But yes, one perceives the resemblance!” He peered eagerly and muttered something else in Portuguese.

Sir John Stevens had an excellent grasp of the language and he winced a little. The phrase was scarcely one that a gentleman would use of a lady. “According to Lord Keywes,” he said stiffly, “the girl was blameless in that affair.”

Winking, the fat old general acknowledged that the little Contessa had been the innocent victim, the version known at the Italian Embassy to the contrary. Adding that in his considered opinion that did not mean she was not a roguish little minx, on the catch for a fortune and a title. Rather unfortunately this speech was in English: old Érico Baldaya prided himself on his grasp of the vernacular.

Mr Jerry Brantwell had gone very red. “I say, sir! Well, beg pardon, I’m sure,” he gulped, as his uncle’s ice-cold eye met his, “but the Contessa is a lady!”

“How you deduce that from ten minutes’ chat in a circulating library I confess I am at a loss to know, Jerry,” noted his uncle coldly.

“Dear boy,” said General Baldaya kindly: “there was nothing wrong with old Jeremy Andrews, of course. But certainly she is a minx, do but look at her!”

“She is not like that!” choked the misguided Mr Brantwell.

Colonel Calhoun looked at his old friend’s face and winced a little. The poor damned boy would be on the mat before he was allowed to crawl into his virtuous bed this evening, or he, Calhoun, was a Dutchman. “Tell me, Throgmorton, who is the handsome lady in the grey?” he said quickly.

Very glad to have the subject changed, Mr Throgmorton told him. And to the relief of most of those present in the elegant old gentleman’s box that evening the topic of the Contessa, minx or not, on the catch for a title and a fortune or not, was allowed to drop.

It was not only the fashionables in the boxes who came to see and be seen, and the pit, this evening, was adorned by not a few unexceptionable partis. Plus the usual nonentities. Gregory Ashenden would unhesitatingly have classed himself with the latter. And had previously informed his old school friends, one Roland Valentine, well connected but comparatively obscure in himself, and Shirley Rowbotham, ditto, that his own humble form would not have been gracing the metropolis this Season at all, had it not been for the gracious invitation from his Cousin Jack to join him, Jack, in his, Jack’s, chambers. Sorry, graciously appointed chambers. His friends had greeted this remark as might have been expected.

Judging by the direction in which his eyes were observed to be focused in the first interval, certain rumours about the said Cousin Jack seemed to be only too well founded. Mr Gregory Ashenden therefore groaned: “Not another one, Jack?”

His cousin’s lips tightened but he said nothing.

Mr Roland Valentine, on his left, had raised his very new quizzing glass. “Aye: gal with Miss B.-D. A peach, ain’t she? Damned like the P.W., hey?”

Mr Shirley looked, and nodded fervent agreement with both these suggestions.

“Well, exact! Another one!” said Greg Ashenden with considerable feeling.

“And we thought he had learned his lesson, with the P.W.,” said Mr Roland sadly.

“Look, shut it, Rollo! I did not invite you to join our party, you invited yourself, and since you are as musical, forgive the phrase, as my left boot, it is beyond my imagination to conceive why you did so!” said the gentleman on Mr Gregory Ashenden’s right heatedly.

The gentleman in question might be the Ashendens’ cousin but, as Greg himself was the first to admit, they themselves were the merest of the mere, being related only on the distaff side, and in fact it was a wonder that Cousin Jack even condescended to be seen in their humble company, he had grown so fine over late years, what with the coats from the hand of Mr Weston, the dashing curricle and four, the membership of the F.H.C., the— At about this point in his flow his cousin had interrupted him with a wisty one to the midriff. Causing Mr Gregory to pant, once the mêlée was over, that one could of course tell that Cousin Jack was used to practise the manly art at the salon of the great Jackson himself. And could his humble self come along, just merely to watch, next time, Jack? Or hold your coat? Thus causing Cousin Jack to offer him another bout on the spot.

“Well, was not doing nothing else this evening. Thought you fellows might care for a hand of whist or some such, later,” Rollo excused his presence at the opera house.

“I am promised to Henri-Louis this evening,” said the Ashendens’ cousin unencouragingly.

Greg gave an admiring gasp. “Henri-Louis! Lor’, next thing we know, Jack, you will be hobnobbin’ with European royalty!”

At this unkind and really almost undeserved crack, for Henri-Louis de Bourbon, if only a minor sprig on that once vast and shady family tree, was royal enough, Mr Rollo and Mr Shirley collapsed in horrible sniggers.

“Shut it,” said Mr Ashenden’s cousin unpleasantly. “And I warn you, Rollo: start snoring or talking during the piece and I’ll throttle you with my bare hands.”

“Taking his op-er-a gloves off to do it, too,” noted Greg admiringly.

“Drop it, Greg,” said his cousin sourly.

“Yessir; immediately, yer Honour; begging yer Honour’s pardon!” he gasped, touching his forelock frantically.

His cousin got up. “I’ll be back,” he threatened, walking off.

“Cousin May was right,” said Greg instantly. “Jack has fallen for that hot-lookin’ little piece. –Well, Lor’!” he said as Mr Shirley opened his mouth. “Look at her! Freddy Bon-Dutton says she cannot be hardly a day over twenty-one, and only look at the rig-out!”

Mr Shirley Rowbotham eyed him drily. “Highly unsuitable for a young widow: oh, quite. You are gettin’ very nice in your old age, Greg.”

Reddening, Greg returned: “No, but Jack ain't nobody, y’know! It won’t do!”

Shirley looked thoughtfully at Raffaella. “Keywes told m’brother Ceddie there is nothing in that rumour.”

Sir Cedric Rowbotham was our former Ambassador to the Prussian court, and quite a power in the land. Certainly as far as Mr Shirley and his cronies were concerned. So Rollo acknowledged: “There you are. If Sir Ceddie believes she didn’t seduce old dell’Aversano, dare say she didn’t. Um, does he believe it?”

“Yes,” replied Mr Shirley definitely. “He said Keywes’s word was good enough for him and he would be obliged if I could refrain— Um, never mind that. Well, dare say the Italian cats was only too glad to get their knives into a ripe young widow. So, there you are, Greg. The girl’s an innocent.”

“That ain’t— Well, that ain’t only the point, old man. In the first place, dare say the story may not be true, but my aunt will never countenance Jack’s allying himself with the sort of girl what gets that sort of rumour spread about her. Nor welcome a daughter of that mother of hers as a daughter-in-law!”

Rollo, ignoring most of this, was peering at Raffaella again. “Ten guineas says we see him next in the little peach’s box.”

“Make it sixpence and I’ll take you,” said Mr Gregory without shame.

“Oh, right you are, sixpence it is,” he agreed amiably.

They watched breathlessly, but Mr Beresford did not appear at Raffaella’s side.

Naturally Miss Bon-Dutton’s box continued to observe the throng during the interval.

“Who is that enchantingly pretty lady with the deep red hair?” asked Raffaella. “In the box with Katie and Nellie Dewesbury.”

Eudora replied with a certain resignation: “That is Lady Rockingham.”

Raffaella stared. The Marchioness of Rockingham did not seem very much older than her humble self. “Really? Then we shall not expect an introduction!” she said gaily. “That is, if you will but tell us: are those the Hammond emeralds?”

“Yes,” said Eudora, wincing.

“You are not looking!” she discerned with a trill of laughter..

“I think I’m not looking because I’ve already observed that imprimis, the Marchioness’s brother, Mr Luís Ainsley, is with them this evening, and he is already quizzing you; secundus, that Sir Lionel Dewesbury is with them this evening; and tertius, that Katie Dewesbury has had the temerity to wave to us under her father’s nose. –And please, please, tell me that Lady Lavinia D. is not with them this evening,” she whispered.

“You are being very silly,” said Raffaella with dignity. “If she were, one would merely bow. But she is not, and actually that is not surprising, for Katie tells me she is tone-deaf.”

“Well, possibly if Lady L. is not here I shall be brave. But I must warn you that Luís Ainsley is a charmer and a lady’s man, whose expectations consist entirely of some damned Spanish estate of his mother’s, and frankly I do not think you would go down at all well with the Spanish aristocracy, Raffaella!”

“Possibly he does not go down very well with them, either, which is why he is here!” she suggested with a loud giggle.

“Er, more than possibly, yes.”

“Tell us who some more of the people are!” she begged, leaning forward eagerly.

Miss Bon-Dutton did not have the heart to tell her not to lean forward like that: Raffaella had admitted she adored the opera, and had been so looking forward to it, and had so missed it since her disgrace and incarceration in the convent. She pointed out more notables. Conceding, as a handsome gentleman and a pretty little brown-haired lady bowed to herself, that they were Lord and Lady Keywes. Yes, lately our Ambassador to Rome.

After a moment Raffaella said: “I never met them. I suppose they do not know me from Adam, after all.”

Eudora hesitated. Then she said cautiously: “I have heard that the Conte dell’Aversano apprised Keywes of the true facts of that case, Raffaella.”

“Not really? Dear old Pietro!” she cried.

“Yes. But I should not expect cards from the Italian Embassy on that account.”

“No—sicuro!” she said with a shrug and a laugh. “Tell me some more.”

“Oh… Well, you remember Lady Anne and Sir Humphrey Dauntry, Lochailsh’s connections? That is his brother, Admiral Dauntry—the large gentleman in the naval dress uniform. I agree he rather resembles General Baldaya,” she agreed as the Contessa suggested the comparison, “and let me just add that the resemblance goes further than mere appearance. –Yes, York, also,” she agreed as Freddy helpfully noted as much. She did not have to point out that Charles Quarmby-Vine knew Admiral Dauntry very well and was quite often to be seen in town in his company, because he then appeared in the Dauntrys’ box. Expectably, Raffaella dimpled and nodded, and Charles, expectably, responded. Also expectably, Admiral Dauntry could clearly be seen speaking urgently to the Captain. Then they both rose.

“Just try and remember that the Admiral is a very senior officer,” said Eudora without hope.

The gentlemen duly appeared and the expected fawning took place, the Admiral being just about as bad as Charles Quarmby-Vine. In fact, given his age and his position in Society, rather worse. However, their gallantries remained well within the bounds of acceptable behaviour. Eudora was just feeling thankful for this when she realised that Raffaella’s hand had clenched on her fan and that she was looking across at Lord Keywes’s box again. Mr Beresford had just entered the box.

“Jack Beresford,” explained the helpful Freddy. “Corinthian. Cuts quite a dash. Keywes is his brother-in-law, Contessa.”

“We met him briefly last summer: he and my nephew Bobby are old friends,” said Eudora on a weak note: Raffaella had now turned her head away from Keywes’s box and was laughing immoderately at some less than witty sally of the Admiral’s.

“It is Lord Keywes who is related to Lady Stamforth, I think?” ventured Miss Hewitt.

“Er—yes,” agreed Eudora with something of an effort. “They are distant cousins.”

Raffaella at this turned her head towards them and said lightly: “What, more connections of connections? –I was saying just recently to Miss Bon-Dutton, Admiral, that there is no working out the impenetrable intricacies of Society at all: indeed, newcomers such as I go about in constant dread of making the most frightful faux pas by mentioning quite the wrong person to the wrong connection, or—or the wrong connection to the right connection, or making assumptions that connections, right or wrong, exist where none do!” She fluttered the eyelashes horribly.

Admiral Dauntry assured her fulsomely that she could not possibly make any sort of faux pas and she obligingly fluttered the fan as well as the lashes at him. Possibly she did not then need to make the point that she was trying hard, with Cousin Eudora’s and Mr Freddy’s help, to learn who was who: Eudora had the feeling that the Admiral and Charles would both have offered their help in any case.

Very fortunately the two naval gentleman were expected back in the Dauntrys’ box for the next act, and mercifully went off to it.

“Fulsome?” suggested Raffaella dulcetly.

“Admiral Dauntry is known for it,” admitted her cousin.

“I am sure! And perhaps the Captain takes his cue from his senior officer?”

Eudora gave in, and laughed. “I suppose they cannot help themselves!”

Hugh Throgmorton, a man of immense tact, did not point out to his companions at the opera that evening that, as Miss Bon-Dutton appeared to be wearing the freesias he had sent her, it would not be inappropriate to look in on her box. Unfortunately General Baldaya, though certainly capable of immense tact when he so wished, had been considerably intrigued by Sir John Stevens’s frosty reaction to his young nephew’s very evident admiration of the luscious little Contessa. Added to which, he was not particularly immune, himself. So in the final interval he suggested happily that perhaps they should take a stroll. Of course he knew Miss Bon-Dutton slightly, and her family quite well; in fact had stayed at Dallermaine Abbey this last summer, at which season it was positively delightful… Mr Throgmorton rose politely and said that he was sure that Miss Bon-Dutton would be glad to see him. At which the old general, with complete insouciance, said to Stevens: “Do, pray, give me your arm, Sir John.”

The baronet, his cold face unreadable, offered his arm politely.

Mr Jerry bounced up happily and said in an artless tone, though avoiding his uncle’s eye: “I say, may I come along, too, General?”

General Baldaya assenting most cordially, they went out in a bunch.

Left alone together in the box, Colonel Calhoun and General Sir Mortimer Sinclair eyed each other somewhat drily. After a moment the older man murmured: “Do feel free to go after them, Calhoun.”

The Colonel returned frankly: “You are too kind, sir. But as in the first instance I have no particular interest in dark-haired little dashers in get-ups a good ten years too old for ’em—beyond a certain natural enjoyment of the spectacle, of course—and in the second I am a happily married man, I think perhaps I won't bother, after all.”

The General’s broad, wrinkled face creased in a smile. “No, quite. –Does your wife not care for the opera, then, Calhoun?”

“No. In fact she don’t care for London, and is spending this month with her married niece down in Kent. Helping the entire complement of female relatives on both sides of the family to admire the new infant,” he explained.

General Sir Mortimer grinned. “I perfectly comprehend.”

“Aye! Well, I quite like a good show, myself, and then, young Roddy, that’s our second lad, was keen to spend a few weeks in the metropolis. Not keen on the opera, however!” he said with a chuckle.

“No. Er—is young Brantwell?” asked the General politely.

At this, regrettably, Colonel Calhoun went into a spluttering fit of the most painful kind. Emerging from it to gasp: “It don’t count if he is or is no, poor young devil!”

Depending on one’s point of view, it could have been considered a trifle unfortunate that at the moment General Baldaya’s party entered Miss Bon-Dutton’s box, Raffaella was in the very act of smacking Lord Geddings’s hand with her fan. Miss Bon-Dutton most certainly felt it to be unfortunate. There was no way in which she could explain to the visitors that Geddings had only been here five minutes and had merely paid her young charge a silly compliment, so over-elaborate as to be both unbelievable and indeed quite harmless, or that Raffaella’s smack was therefore not positive over-encouragement, or… Bother.

She effected introductions with as good a grace as she could muster and was not surprised to see that the florid old General Baldaya was immensely struck by Raffaella; indeed, “overcome” would scarce be too strong a word.

Sir John Stevens, though not appearing overjoyed to see herself or Raffaella again, bowed politely. Raffaella, thank goodness, merely smiled archly at him, refraining from impertinent comment. Eudora was reduced to asking feebly how he was enjoying the opera. Sir John replied colourlessly and properly and then engaged Miss Hewitt in entirely blameless chat. It was not particularly marked—certainly not so much as to be taken for a snub—but on the other hand… Eudora, in short, did not know what to feel.

Young Mr Brantwell, even though he must know that his uncle was noting his every move, made straight for Raffaella’s feet and worshipped at them. The phrase “making hay while the sun shines” sprang forcibly to mind.

After about ten minutes of this sort of torture approximately a dozen fribbles, largely in dress uniform, invaded the box on the excuse that they were the oldest friends in the world of Freddy Bon-Dutton, and surrounded Raffaella. And Geddings excused himself, noting that he did so hate crowds. Raffaella merely laughed but it would have been no better—in fact, worse—had she sighed.

The man had the immense to gall to say to Sir John as a parting shot: “Dare say we shall meet again very soon, Stevens. At Philippi, if not positively in the Cabinet room.”

Sir John merely responded calmly: “I dare say we shall.”

“Sir John, how wonderfully cool!” carolled Raffaella across the box. “Does it take a lifetime of practice, or does it come naturally to an English aristocratico?”

“I have no idea,” he said with an ice-cold glance.

“Er, why don’t you ask one, Raffaella ?” said Eudora hurriedly.

Raffaella at this collapsed in gales of giggles and the fribbles surrounding her followed suit, so possibly this had not been as misguided an effort as Eudora had felt it to be. She attempted to avoid everybody’s eyes and in fact was driven to consult her programme blindly…

When the opera was over Eudora was very thankful just to creep into the carriage and head for quiet Adams Crescent. Assuring the gallant Freddy as he handed them into the carriage that they truly did not need his escort and he wished to go off to play cards with his cronies, he must do so. And waving him off with, it must be admitted, considerable relief.

“What a pity that that lovely old General Baldaya is not forty years younger and forty stone lighter!” gurgled Raffaella.

“Just don’t, please,” she said with a sigh.

“You do not have the headache, do you?”

“No.”

After a moment Raffaella ventured cautiously: “Geddings was not so very bad.”

“Given his reputation, positively restrained. –Well, with regard to his conduct towards yourself, certainly.”

Raffaella swallowed. “I thought it was very funny, what he said to Sir John.”

“Some of us did notice that,” she sighed.

Raffaella, of course, was all the more annoyed with Sir John because of her notion that he would be an excellent match for Eudora. “I apologise for—for embroidering on it, but in my opinion he is a cold beast and horrible!” she cried furiously.

“We noticed that, too,” she murmured.

“Cousin Eudora, he looked down his nose at you!” cried Raffaella.

“My dear Contessa, I think you are exaggerating,” objected Miss Hewitt.

Eudora sighed. “I really don’t think there was anything to remark in his manner to me, Raffaella. His is not a warm personality, in any case.”

Raffaella scowled, but was silent.

“It is just… Well, if you could just manage not to encourage little Jerry Brantwell, Raffaella, I think possibly that might—might mollify Sir John. In the case,” said Eudora in a voice which trembled in spite of her best efforts, “that we have to face him again.”

“I don’t think I was encouraging him, exactly. Well, next time we see him I shall be very cool.”

“Mm.” Eudora was aware that Raffaella was still scowling over it, but she did not feel herself to be capable of insisting, and so said no more.

It being a Tuesday, most of the gentlemen who had been told they would be at home on a Tuesday had called. Miss Hewitt had gone into a mild panick, fearing there would not be enough teacups for them all, but Eudora had murmured that she did not think they had come for tea, and Miss Hewitt, though gulping slightly, had relaxed.

“Huzza!” cried Raffaella unaffectedly, bouncing up as the footman announced Lady Laetitia Lacey, Miss Dewesbury, Miss Nellie Dewesbury, and Mr Charles Grey. “You came!” She rushed over to them and kissed Katie and Nellie affectionately, deserting young Captain Paxton, who had been in the middle of a flowery compliment.

Mr Charlie Grey expressed himself very glad indeed to meet the Contessa; Raffaella replied blithely: “Oh, and I, of course, sir. Only I confess, I cannot remember just who you are. Except that you are one of the Greys, sicuro!”

Mr Grey’s long hazel eyes sparkled, and he did not appear in the least put out by this greeting. “Frightfully well connected, though negligible in himself: would that call anything to mind?”

Raffaella fluttered her lashes. “I am sure it ought to, sir, but we had such a lot of cards.”

“I am entirely flattered that you should have remembered that one of them was mine,” he said, bowing.

The arrival of the three young ladies succeeded in heartening those gentlemen who had not managed more than to hover on the fringes of the group surrounding the Contessa, and things were going along quite well, though Eudora, for one, would not have dignified it by the name of “salon”, when the door opened and Nettle announced: “Mr Jeremy Brantwell; Mr Roderick Calhoun.” And two very young men in very choking neckcloths and blinding waistcoats came in, looking very self-conscious. Jerry Brantwell, very evidently, had roped a friend into his escapade. Mr Calhoun appeared the more at ease so possibly he might be older. Say, twenty. Resignedly Eudora went to greet them. Not so much as bothering to formulate the hope that Raffaella would not smile at the little idiots in that warm way….

Eventually, the room having cleared a little, those who had arrived very early mostly taking their leave—apart from Captain Quarmby-Vine, who was looking at Raffaella very much as a hungry dog does a bone—Eudora was able to sit down by Katie on a sofa.

“Well, no: no idea at all,” murmured that damsel before she could speak.

Eudora swallowed. “I was merely going to say, are you quite sure that her Ladyship would approve this little visit?”

“I am very sure she would not. Papa heard at White’s that you had taken a house for the Season, and she forbade both Gwennie and me expressly to call, once she had ascertained who your guest was,” returned Katie calmly. “Not Nellie, of course, as it would not occur that anyone who was only just out would have the temerity to pay calls in London unaccompanied,” she noted with a dryness worthy of Lady Lavinia herself.

“In that case, though of course I am very glad to see you, I feel I must say you should not be here.”

“Thank you,” said Katie calmly, smiling a little. “And now, may I ask if you are pleased with the house, Miss Don-Dutton?”

“What? Oh—well, yes, very,” replied Eudora feebly. She could not help feeling quite out-manoeuvred, and reflected that in her quiet way, little Katie was bidding fair to be as managing as her mamma. Well, quite possibly that was what the gallant Commander Sir Arthur Jerningham needed, she thought with a little smile, rising to greet him as he was announced. And assuring him that it was not at all too late to call. She thought he knew most of those here? He thought he did, too, and did not ask for introductions, merely nodded to acquaintances and made straight for Miss Dewesbury’s side. Ousting Mr Calhoun by a whisker. And not appearing discouraged by Miss Dewesbury’s coolly calm greeting.

Clearly Katie and Nellie would have liked to stay on a little to gossip with Raffaella, but they rose politely when Lady Letty did. If anyone in the room was surprised when Commander Sir Arthur and Mr Roderick Calhoun both volunteered to assist Mr Charlie Grey to escort the young ladies home, they must have been blind as well as stupid. But Eudora did not think there were any such present.

“At least Geddings didn’t come,” she said to Miss Hewitt with a groan when it was all over, and Mr Jerry Brantwell had been positively turfed out of the house.

“He has the reputation of not caring to make one of a crowd,” returned that gentle lady on a dry note.

“Oh, absolutely! Well, let us thank God for it. It was quite bad enough with young Brantwell turning up. Would there be any use in begging you—and I am quite prepared to go on bended knee—to discourage the young imbecile?” she said to Raffaella

“He is the sort of young imbecile who does not recognise it, alas!” she replied with a merry laugh. “Was it not all delightful? And for next week”—Eudora closed her eyes—“Mr Charlie Grey has absolutely promised to bring his mandolin, and Commodore Gatenby is threatening an ode—he is witty and intelligent, such a pity he's married, isn’t it?—and Lady Letty has promised that they will bring a Mr Johnny Cantrell-Sprague, who knows Mr Coleridge. Did he leave a card? I cannot remember, though I am sure I have heard the name.”

“Connections of the Vanes—Stamforth’s family. And the Greys,” said Eudora with her eyes shut. “And on the distaff side of this particular Cantrell-Sprague, the Hammonds. His grandmother was a sister of the present Marquis of Rockingham’s grandfather.”

“Oh? What a pity he is only a Mister!” returned Raffaella gaily.

Eudora groaned.

Miss Hewitt must have been mulling things over since the evening at the opera, for, Raffaella not having come down to breakfast after a late night, she ventured: “My dear Miss Bon-Dutton, I may be reading too much into this. But did you not remark something particular in the Contessa’s manner when we caught sight of Mr Beresford at the opera?”

Eudora sighed. “Yes. I have been trying to tell myself I was imagining it.”

“My dear, it would not do,” she said with a troubled look.

“Quite,” said Eudora heavily.

“Er… And Mr Jerry Brantwell?”

“Just pray,” said Eudora heavily, “that no-one of our Tuesday callers knows his uncle.”

“Oh, dear!” Miss Hewitt lamented.

Eudora took a deep breath. “Although any serious involvement there would not do, Miss Hewitt, we should not let this thing get out of proportion. Indeed, we should not let ourselves be influenced by Stevens’s view of the matter.”

“But my dear—” she quavered.

“We have as much right as any persons in London to entertain whom we please. And whatever stories Stevens may have heard about Raffaella—and whatever her mother might be—she is certainly innocent of any wrongdoing.”

“Of course!” she agreed strongly, her thin cheeks flushing.

“There you are, then,” said Eudora mildly. “If I show any signs of flinching should we encounter Sir John in the future, pray recall my own words to me. In fact, the mere uttering of the word ‘innocent’, would do. May I trouble you for the strawberry conserve?”

Miss Hewitt passed it, her eyes sparkling in a somewhat militant manner. “Of course, my dear Miss Bon-Dutton, you are so right! But it shall not be ‘innocent’, that would be too obvious; we shall have a—a password!”

Eudora coughed. “A password—yes.”

“‘Rome’? No-o… Ah! ‘Rome was not built in a day!’” she beamed. “I shall just say it… casually, you know!”

Casually, yes. Difficult though it was to envisage a conversation into which the phrase might be casually inserted with anything like verisimilitude, Eudora agreed feebly: “Splendid.”

“I shall say it whenever either of us lapses,” she decided firmly. “For we must not forget whose side we are on!”

“In this campaign we seem to be waging?”

Miss Hewitt nodded her faded head grimly. “Of course. For what else is it?”

Miss Bon-Dutton smiled feebly. What else, indeed?

Next chapter:https://raffaella-aregencynovel.blogspot.com/2022/11/the-salon.html

No comments:

Post a Comment